1930s Anti-Jewish Sentiment: Not Just in Germany

Liberation of theConcentration Camps: A Cause for Celebration

As Soviet, American, and Britishforces moved further into Germany and German-occupied territories, they beganto encounter the concentration camps — and the evidence of mass murder therein.Auschwitz, liberated by the Soviets on January 27, 1945, was the first camp tofall. As Allied forces closed in, German leaders ordered that camps on the edgeof their territories be forcibly evacuated and the prisoners — those whosurvived the “death marches,” at least — moved to camps deeper in the Reich inorder to cover up the Schutzstaffel's crimes.

For example, in May of 1945, the SSwas holding more than 7,000 prisoners from Neuengamme, Germany on two ships:a Kraft durch Freude luxury cruise ship (designed to hold just800 or so passengers) called the Cap Arcona and a cargo shipcalled the Thielbeck. With no food or water on board (except,presumably, for the guards and crew), there was little chance for survival.Tragically, on May 3, British troops, assuming the Cap Arcona andthe Thielbeck carried German troops, bombed both ships. Bothcapsized, killing all but about 7,000 of the prisoners aboard. (source)

To the Nazis, of course, these deathsmeant there would be nobody left to tell the world what they’d done. But it wastoo late. In April of that year, US troops liberated Dachau and Buchenwald,while British forces liberated Bergen-Belsen. By the summer of 1945, Alliedarmies had liberated all of the major and satellite camps.

As the death camps were cleared outand the survivors removed to safety, there was plenty to celebrate, and the joywas contagious as this grotesque chapter of history drew to a close.

The RainbowDivision

The Forty-Second Infantry Division ofthe US Army National Guard, nicknamed the “Rainbow Division” because it wascomprised units from several states that didn’t have their own divisions,liberated Dachau, the longest-running concentration camp in Germany, on April25, 1945, and the commemorative materials it produced shortly thereafter werereflective of celebrations taking place among Allied troops and Jewishcommunities the world over.

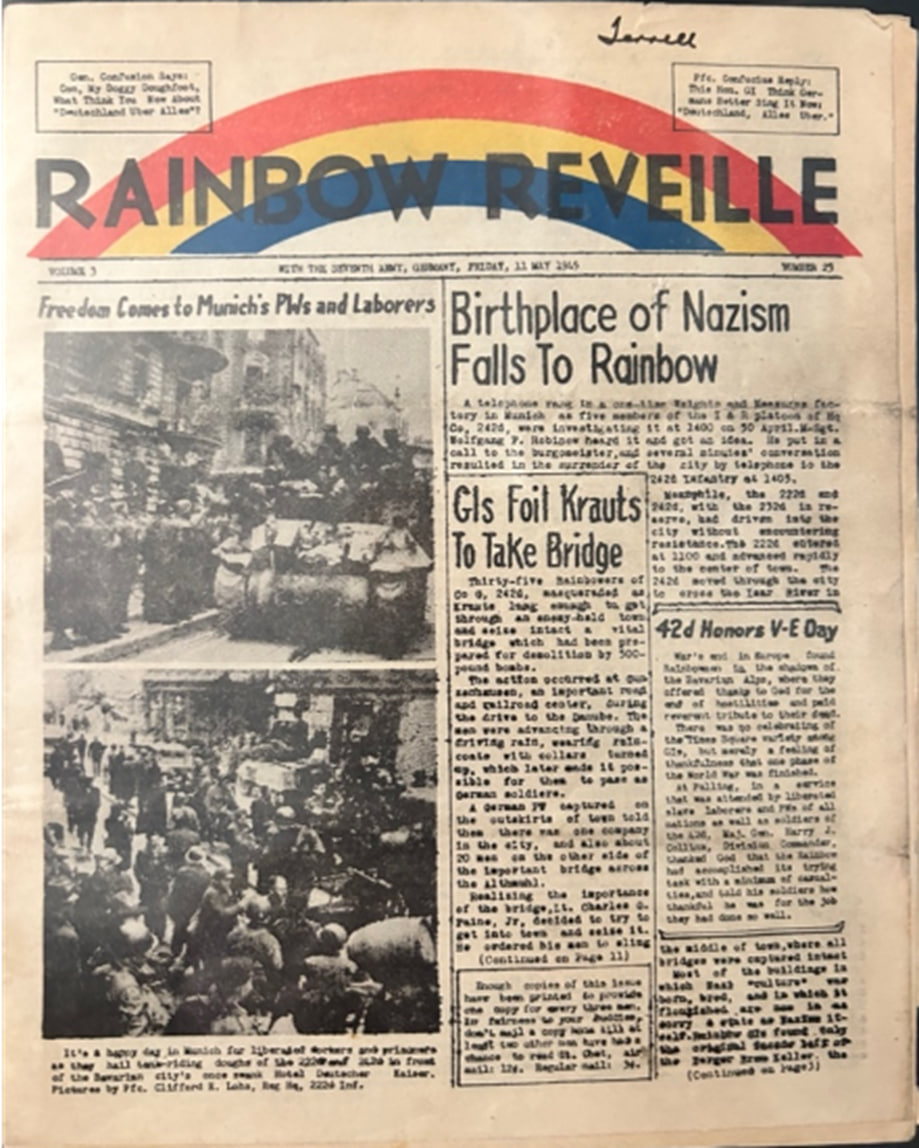

The May 11, 1945 edition of The RainbowReveille, the newsletter published by the forty-second, celebrates the endof the war in Europe, highlighting the Rainbow Division’s individual successesas well as VE Day, during which, the paper reports, “There was no celebratingof the Times Square variety among GIs, but merely a feeling of thankfulnessthat one phase of the World War was finished.” The inside of the newsletteroffers a more somber look at the liberation of Dachau, including the history ofthe camp and the first photographs taken within its walls (taken by Reveillephotographer Private First Class William R. Hazard). As we’ll see in thischapter, the joy and relief that came from the end of the war in Europe wastempered by the discovery of the depth of the Nazis’ barbarism.

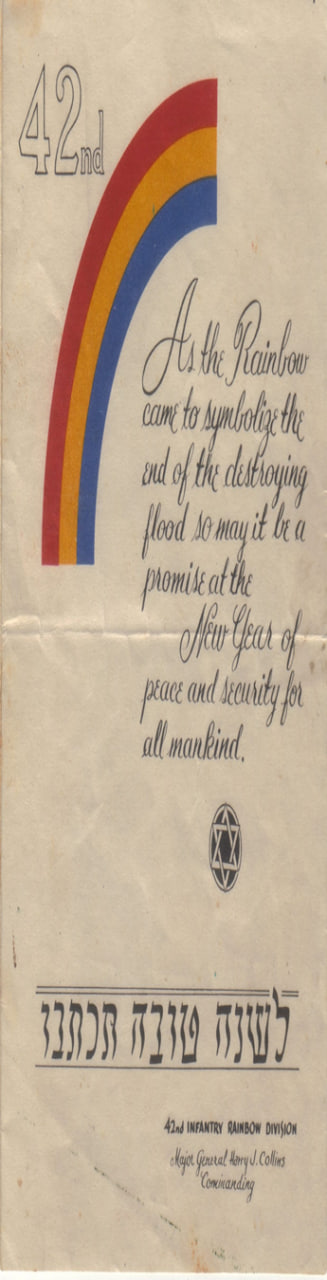

Though the Rainbow Division’s nickname predated itsmarch into Germany, the prescient symbolism — echoing the Genesis story ofGod’s covenant to never again destroy the world — was not lost on the soldiers.This Shana Tova card (for the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah)sent from 42nd Infantry Major General Harry Collins commemorates that covenant,expressing hope for peace in the new year — and the new era begun by theliberation of the concentration camps and the end of the war in Europe.

Our Rainbow Division collection is onewe’re quite proud of. I amassed a selection of the colorful maps — of which twowere given to each division member — through careful, specific searching, and Iwas pleased to be able to give one to the US Holocaust Museum. And the ShanaTova card is one of my favorite items; I’ve never seen another one in all myyears collecting.

But, of course, the Rainbow Divisionwas just one group of liberators from the United States Army.

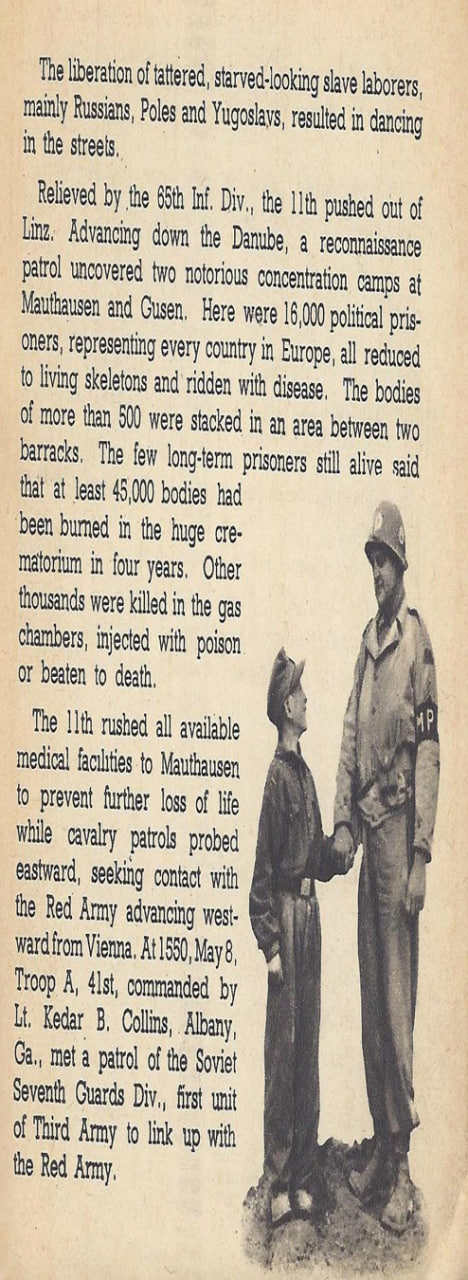

The 11th Armored Division, nicknamed “Thunderbolt,”liberated Austria’s Mauthausen and Gusen concentration camps in May of 1945,freeing thousands of prisoners. This thirty-two page softcover book tells thestory of the rescue — and it also sheds additional light on the unspeakableatrocities the troops witnessed in the camps.

On May 1, 1945, just one week before VE Day, The Starsand Stripes, the US Armed Forces’ daily newspaper, celebrates the USseizure of Dachau, along with the capture of Munich by the US Army, Sovietattacks on Berlin, and the promise of an impending offer of surrender fromHeinrich Himmler.

The Philipson Family Connection

Among the soldiers celebrating the endof the death camps was Gregg’s father, Bernard Philipson, who served in theU.S. Army 8th Armored Division, which liberated Langenstein, a subcamp thathoused prisoners who had been transported from Buchenwald and other campsbeginning in April of 1944 (source).Bernie came back from the war andwent right to work, focusing on providing for his family despite strugglingwith what we now recognize was post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Look andWeep”

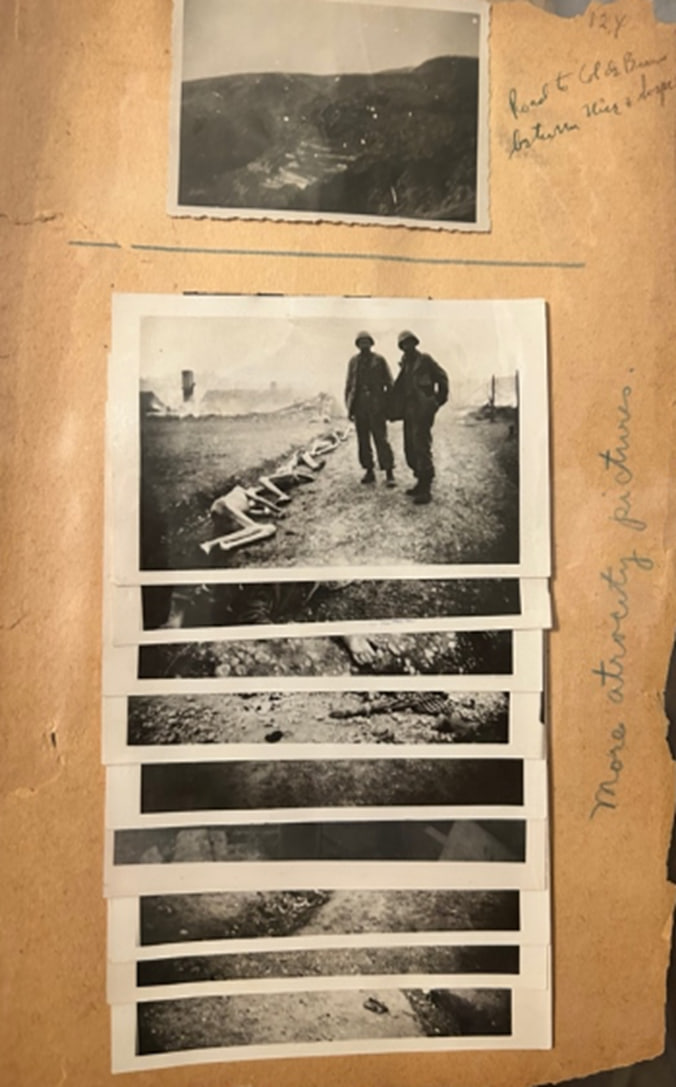

Excerpts from a scrapbook created by a Jewish Americansoldier named Alex Sesonske. His uncensored scrapbook, which includeseverything from training camp photos to letters from his relatives to a poemhis mom wrote, mocking his mustache, is one of the most complete accountsavailable of the GI experience during WWII. Though Sesonske doesn’t name thecamp where these photos are taken, we can infer from his caption, “…taken at aConcentration Camp near Landsberg, Germany…” that they were of Kaufering, asubcamp of Dachau. He affixed them to his scrapbook in overlapping fashion,presumably to avoid shocking himself or anyone else with the gruesome imageshe’d saved.

The liberation of the concentrationcamps was, of course, a cause for celebration: the killing was almost over, andthe Fürher was dead. However, the Nazis had been so meticulous about hiding theextent of the atrocities they were committing at their “death mills” thatliberation was the first time outsiders saw what was truly happening to Jewsand other political scapegoats in Germany and German-occupied Poland andAustria. As such, the victory of liberation was undermined by the bone-deepshock of discovering the truth. And as for the survivors, well,anything resembling normalcy was still a long way off.

Sesonske’s captions above, “Look andweep,” and “Lest we forget” encapsulate a sentiment that was common amongliberators and still rings true today, a driving purpose of the PhilipsonCollection: only by bringing the “evidence” to light — and very intentionallyremembering and learning from it — can we ensure that history doesn’t repeatitself.