How did anti-Jewish sentiment get so systematized? How did the prejudice become so widespread? The hate so vitriolic?

When we think about “how the Holocaust happened,” those are the kinds of questions that come to mind. Those are the questions we hear from children and adults alike. “How did it get so bad?” “How did the power of the Nazis (and their far too many collaborators) become so great that they could murder 6 million Jewish people before anybody could stop them?”

It comes down to radicalization: the process of leading individuals and groups to adopt extreme viewpoints against certain people, political stances, or religions. In this case, we’re talking about radicalization of German citizens against Jewish people (though it wasn’t just the Germans, and they didn’t hate only the Jews, as we’ll see later).

The Three Pillars of Radicalization in Post-WWI Germany

Radicalization doesn’t happen in a vacuum; it’s not a sudden, spontaneous change in a person or group. Rather, it tends to occur under a specific set of circumstances, defined by AW Kruglanski (2019) as the three pillars of radicalization:

1. Need: The individuals’ desire for personal significance

2. Narrative: The stories or philosophies that guide those individuals in their quest for significance

3. Network: A group that validates its members and rewards them for embracing the narrative

In post-WWI Germany, all three pillars were in place, making the territory the perfect breeding ground for the Nazi party’s hatred.

In terms of need, Germany, as a whole, had lost significance on the global stage due to the political, social, and economic consequences of WWI, the instability and general distrust of the Weimar republic, and the economic upheaval of the Great Depression. The German people “needed” to regain their status and superiority; they were primed for a new ideology, a new leader, and a new scapegoat. And, despite their integration and active participation in German society — despite their full participation in WWI — the Jewish people became that scapegoat.

As far as network goes, well, that’s a whole other article — and one we’ll share soon — on how the Nazi party took control of every facet of German culture.

But for now, let’s focus on narrative. Because the Nazis sure did craft a narrative that cast the Jewish people as the root of all evils. But here’s the thing: they didn’t actually craft that narrative. None of the anti-Jewish propaganda that came out of Nazi Germany was new. Now, some of it may have been repackaged for the times, but it had all existed long before Hitler started spewing it.

The tactics, imagery, etc. the Nazi party used to “other” and dehumanize the Jewish people were not new — anti-Jewish propaganda dates back to medieval times — but the current social and political environment gave the efforts unbridled power.

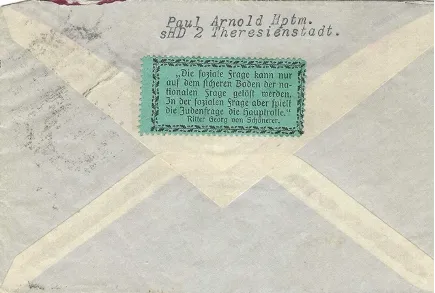

Nazi Symbolism, Before the Nazis

The Swastika: A Perverted Symbol of Good Luck

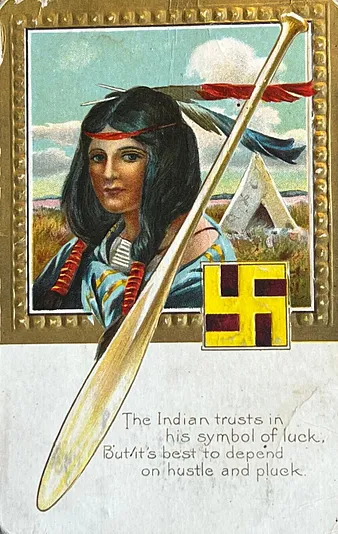

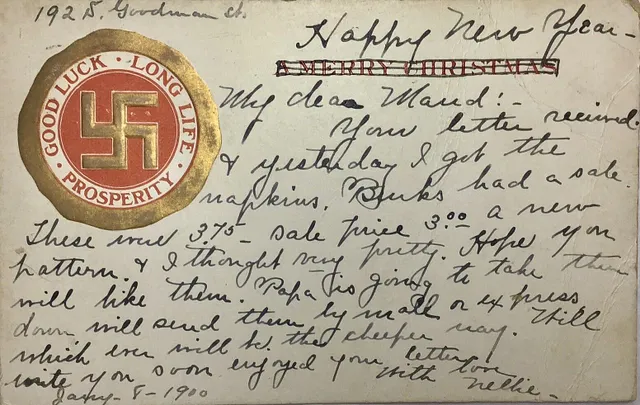

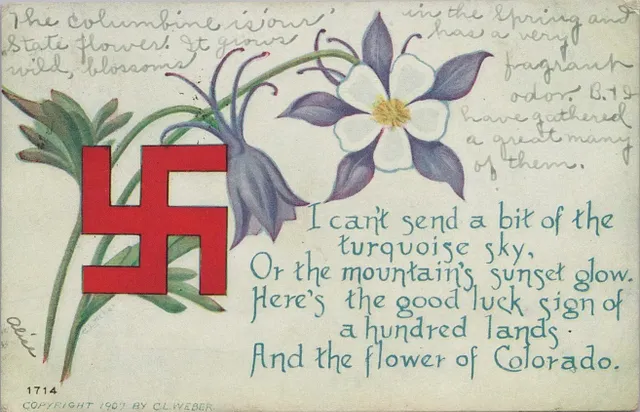

Even the Swastika, today the most identifiable symbol of hatred in the world, is an ancient rune, dating back as long as 7,000 years ago in Eurasia.

While most of the Nazi imagery and storytelling was just old hate recycled and amplified, the Swastika is different in that it began as a positive symbol. It was — and still is, in fact — a sacred symbol to many eastern religions, and it has a long history in Native American and pre-Christian European culture, as well. Before the Nazis perverted it, the Swastika was a symbol of good luck for these cultures.

The Swastika as a Symbol of Good Luck & Auspiciousness

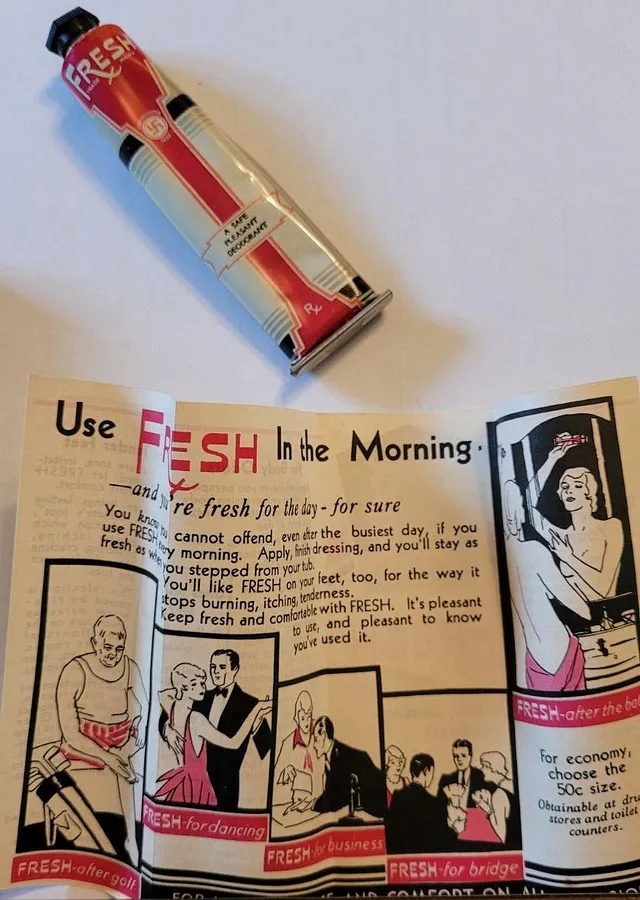

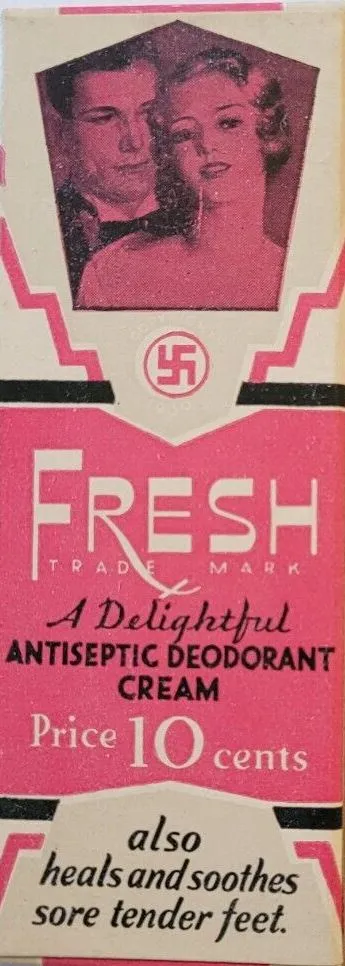

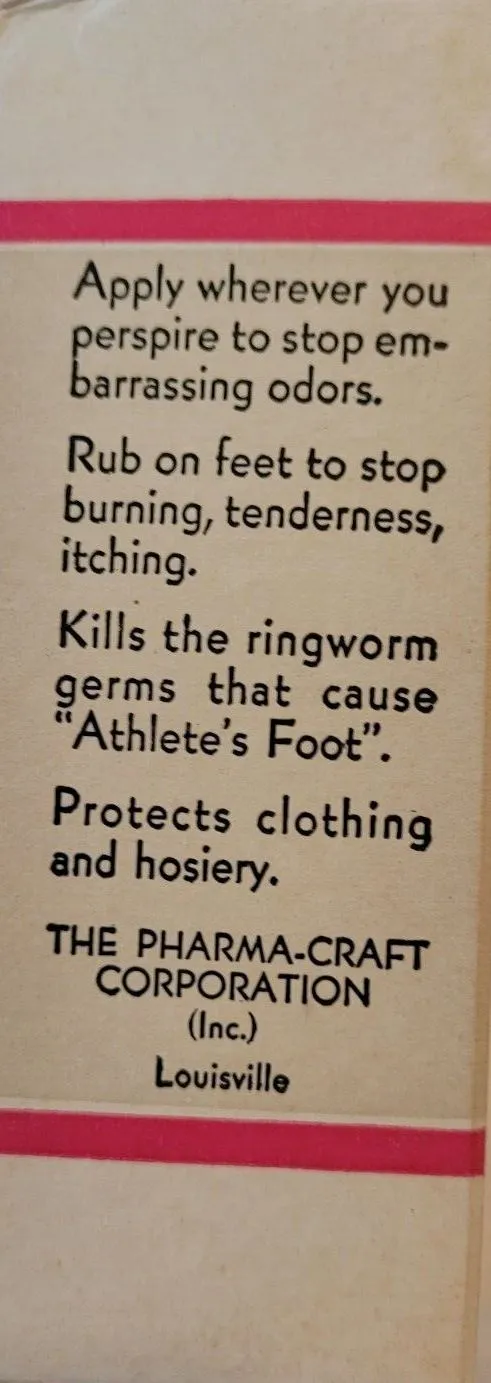

The Swastika as a Symbol of Freshness

A rare item, this deodorant cream boasts the Swastika as a symbol of freshness.

The Swastika Today

Of course, when the Nazis got ahold of it, adding it to their armbands, hats, flags, and more, the Swastika’s original meanings faded away in favor of what we recognize it for today: a despicable image of hate.

Anti-Jewish Tropes: A Tale As Old As Time

Anti-Jewish tropes, also known as “canards,” are defamatory stereotypes of the Jewish people, at best the basis for nasty jokes and, more often, the foundation for widespread persecution. Some of the more common tropes — we might call them “conspiracy theories” today — include the idea that Jews were collectively responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus (as depicted in the Oberammergau Passion Play, which began in the 1630s), that Jews caused the Black Plague, that Jews were responsible for the spread of Communism, and that Jews are continuously plotting to take over both the news media and the world.

Sadly, even the most gruesome tropes persist today. When I visited a church in Poland, I was unsurprised to find allegations of Blood Libel (the grotesque notion that Jewish people use the blood of non-Jewish children for ritual purposes) still affixed to the wall inside, albeit halfheartedly hidden by a moveable screen. I haven’t included images in this book because I was sternly forbidden from photographing that part of the church.

While, as we know, these tropes far predate the Holocaust, they poured fuel on the fire of Hitler’s particular brand of prejudice.

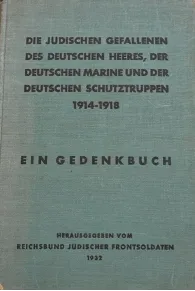

The newspaper and book pictured below highlight one trope that was instrumental in building anti-Jewish sentiment in Germany after WWI, even though it was easily disproved with data. That’s the myth that Jews went out of their way to avoid fighting in WWI. The Nazis’ used this particular trope to their great advantage in casting Jews as their scapegoat, though the two images below show just how easy it was to prove false: in fact, Jews were well represented in the German military during WWI, and this was true in the United States, too. Though the narrative would persist that Jews were ducking the war, the reality was that the percentage of Jews per capita in the US military was larger than the per capita percentage of Jews in the United States.

Die Jüdischen Gefallenen is a memorial book listing every Jewish person who died fighting for Germany in WWI. German nationalists had demanded an accounting of the Jews who had died serving the armed forces in WWI, expecting that it would show underrepresentation of German Jews in the military. The results, however, proved the opposite, so the nationalists tried to suppress the findings. We suspect that the RJF published them with the intent to counteract German allegations that the Jewish people had ducked their obligations to support Germany in WWI.

Der Schild was a German newspaper published by a group of Jewish soldiers who’d served on the front lines in WWI, the Reichsbund Juedischer Frontsoldaten (RJF), who both emphasized German patriotism and stood against brewing anti-Jewish sentiments. This particular issue, published February 7, 1936, highlights the Jewish combat airmen in the German airforce.

Dehumanization

Following the appalling spirit of centuries of anti-Jewish sentiment and tropes, the narratives the Nazis propagated about the Jewish people in the leadup to the Holocaust were wildly varied — and all despicable. Jews were painted as usurers, traitors, philanderers, political puppet masters, and more. The Jewish people were even blamed for the housing shortage in Germany.

In all of their propaganda, the Nazis went to great lengths to use these age-old tropes and conspiracy theories to dehumanize the Jewish people, turning them into grotesque caricatures meant to be mocked and reviled by children and adults alike.

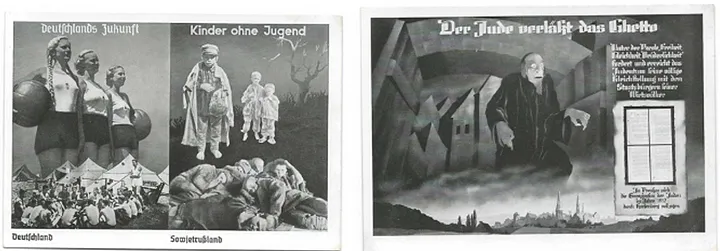

Postcards like these, produced by the propaganda bureau of the national socialist party (the Nazi party) and labeled NSDAP on the back, were ubiquitous. The left is a brutal comparison of German children — athletic, proud — to Jewish children who are depicted as dirty, lazy, and poor. The right depicts a caricaturized, Golem-esque Jewish man trudging out of the ghetto. While in Jewish folklore dating back to Medieval times, a Golem is a protector formed of inanimate material (such as mud), the early twentieth century saw Golems used in German films and other propaganda as something terrifying, as depicted here: a monster to be feared (source).

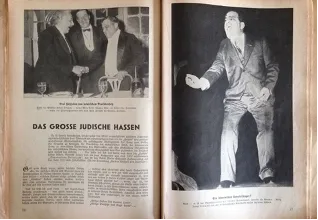

Der Ewige Jude (“The Eternal Jew”), an anti-Jewish film produced by the German Ministry of Propaganda, is emblematic of that dehumanization narrative. The faux documentary is despicable, frame for frame, with highlights including the comparison of Jewish people to disease-carrying rats, “alien”-like caricatures of the Eastern European Jewish culture, and footage of Hitler’s infamous January 1939 Reichstag Speech promising the “annihilation of the Jewish race” in Europe (source).

Our focus in this article is on how the foundation of the Nazis narratives was entirely unoriginal. They simply rehashed old stories — stories that are still circling today — to villainize an entire culture. So we’ll leave it there for now. But there is so much more to say on the way the Nazis used these old stories, tied up in new packaging, as propaganda to dehumanize the Jewish people and further the narratives that Jews were to blame for every problem facing the German people. We’ll share more soon on how propaganda passed through the mail — targeted at Germans, citizens of other countries, adults, and children — acted as the 1930s and 1940s version of social media, and how the Nazis made sure their messages went viral.