As Soviet, American, and British forces moved further into Germany and German-occupied territories, they began to encounter the concentration camps — and the evidence of mass murder therein. Auschwitz, liberated by the Soviets on January 27, 1945, was the first camp to fall. AsAllied forces closed in, German leaders ordered that camps on the edge of their territories be forcibly evacuated and the prisoners — those who survived the “death marches,” at least — moved to camps deeper in the Reich in order to cover up the Schutzstaffel's crimes.

For example, in May of 1945, the SS was holding more than 7,000 prisoners from Neuengamme, Germany on two ships: a Kraft durch Freude luxury cruise ship (designed to hold just 800 or so passengers) called the Cap Arcona and a cargo ship called the Thielbeck. With no food or water on board (except, presumably, for the guards and crew), there was little chance for survival. Tragically, onMay 3, British troops, assuming the Cap Arcona and the Thielbeck carried German troops, bombed both ships. Both capsized, killing all but about 7,000 of the prisoners aboard.

To the Nazis, of course, these deaths meant there would be nobody left to tell the world what they’d done. But it was too late. InApril of that year, US troops liberated Dachau and Buchenwald, while British forces liberated Bergen-Belsen. By the summer of 1945, Allied armies had liberated all of the major and satellite camps.

As the death camps were cleared out and the survivors removed to safety, there was plenty to celebrate, and the joy was contagious as this grotesque chapter of history drew to a close.

The Rainbow Division

The Forty-Second Infantry Division of the US ArmyNational Guard, nicknamed the “Rainbow Division” because it was comprised units from several states that didn’t have their own divisions, liberated Dachau, the longest-running concentration camp in Germany, on April 25, 1945, and the commemorative materials it produced shortly thereafter were reflective of celebrations taking place among Allied troops and Jewish communities the world over.

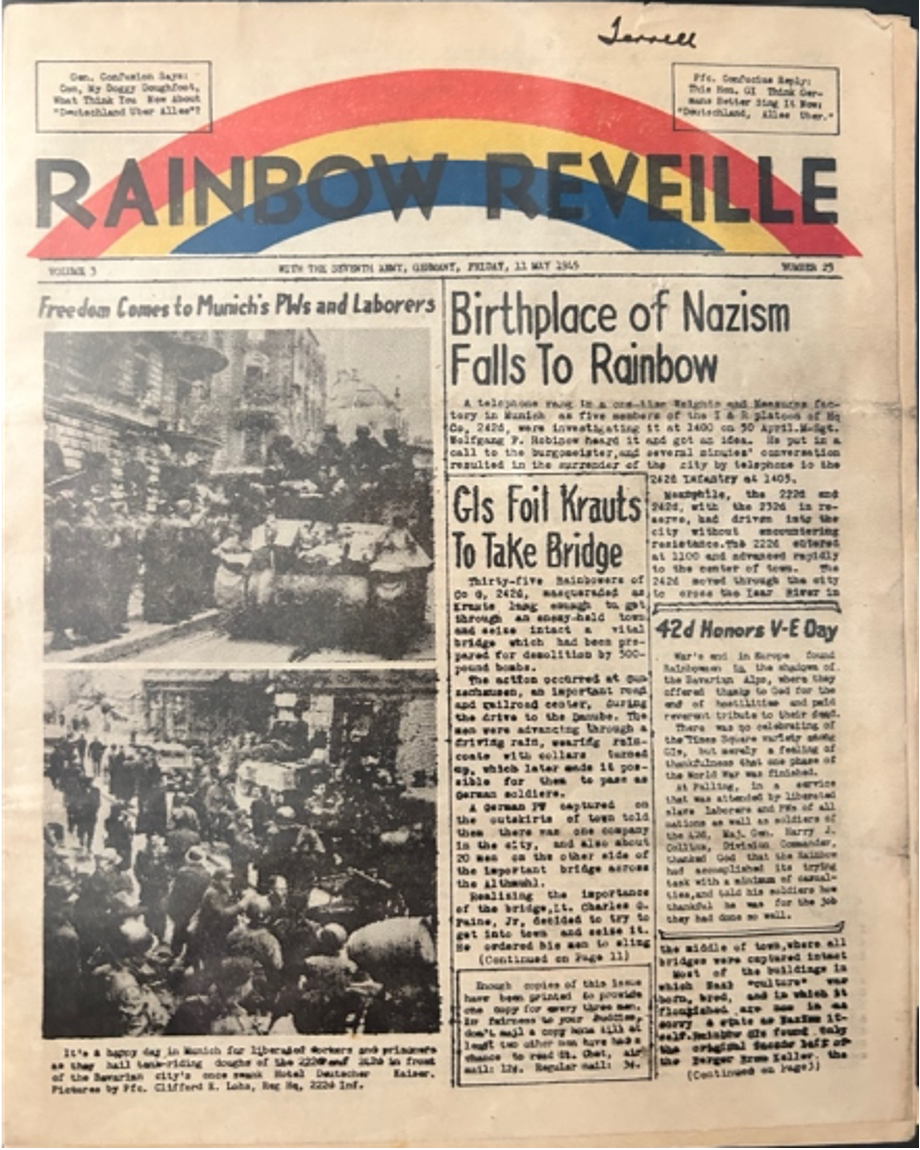

Pictured below, the May 11, 1945 edition of The Rainbow Reveille, the newsletter published by the forty-second, celebrates the end of the war in Europe, highlighting the Rainbow Division’s individual successes as well as VE Day, during which, the paper reports, “There was no celebrating of the Times Square variety among GIs, but merely a feeling of thankfulness that one phase of the World War was finished.” The inside of the newsletter offers a more somber look at the liberation of Dachau, including the history of the camp and the first photographs taken within its walls (taken by Reveille photographer Private First Class William R. Hazard). As we’ll see in this chapter, the joy and relief that came from the end of the war in Europe was tempered by the discovery of the depth of the Nazis’ barbarism.

%20-%20Sarah%20Welch.png)

Though the Rainbow Division’s nickname predated its march into Germany, the prescient symbolism — echoing the Genesis story ofGod’s covenant to never again destroy the world — was not lost on the soldiers.This Shana Tova card (for the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah) sent from 42nd Infantry Major General Harry Collins, commemorates that covenant, expressing hope for peace in the new year — and the new era begun by the liberation of the concentration camps and the end of the war in Europe.

Our Rainbow Division collection is one we’re quite proud of. I amassed a selection of the colorful maps — of which two were given to each division member — through careful, specific searching, and I was pleased to be able to give one to the US Holocaust Museum. And the Shana Tova card is one of my favorite items; I’ve never seen another one in all my years collecting.

But, of course, the Rainbow Division was just one group of liberators from the United States Army.

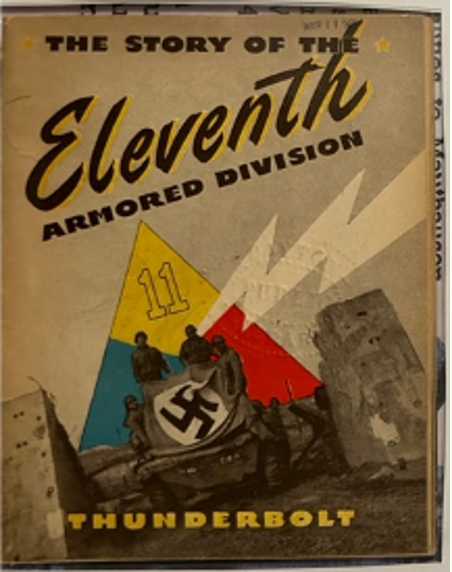

The 11th Armored Division, nicknamed “Thunderbolt,”liberated Austria’s Mauthausen and Gusen concentration camps in May of 1945, freeing thousands of prisoners. This thirty-two page softcover book tells the story of the rescue — and it also sheds additional light on the unspeakable atrocities the troops witnessed in the camps.

%20-%20Sarah%20Welch.webp)

The Philipson Family Connection

Among the soldiers celebrating the end of the death camps was Gregg’s father, Bernard Philipson, who served in the U.S. Army 8th Armored Division, which liberated Langenstein, a subcamp that housed prisoners who had been transported from Buchenwald and other camps beginning in April of1944 (source). Bernie came back from the war and went right to work, focusing on providing for his family despite struggling with what we now recognize was post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Look and Weep”

The liberation of the concentration camps was, of course, a cause for celebration: the killing was almost over, and the Fürher was dead. However, the Nazis had been so meticulous about hiding the extent of the atrocities they were committing at their “death mills” that liberation was the first time outsiders saw what was truly happening to Jews and other political scapegoats in Germany and German-occupied Poland and Austria. As such, the victory of liberation was undermined by the bone-deep shock of discovering the truth. And as for the survivors, well, anything resembling normalcy was still a long way off.

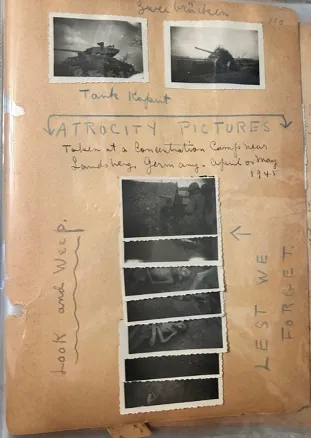

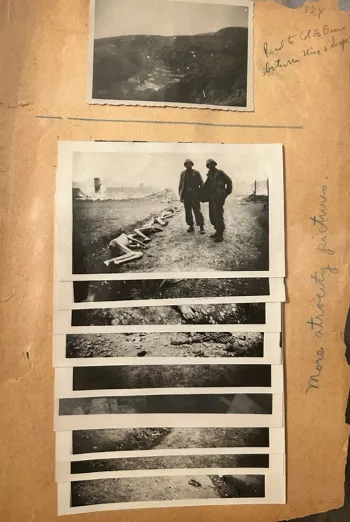

The following images are excerpts from a scrapbook created by a Jewish American soldier named Alex Sesonske. His uncensored scrapbook, which includes everything from training camp photos to letters from his relatives to a poem his mom wrote mocking his mustache, is one of the most complete accounts available of the GI experience during WWII. Though Sesonske doesn’t name the camp where these photos are taken, we can infer from his caption, “…taken at a Concentration Camp near Landsberg, Germany…” that they were of Kaufering, a subcamp of Dachau. He affixed them to his scrapbook in overlapping fashion, presumably to avoid shocking himself or anyone else with the gruesome images he’d saved.

Sesonske’s captions above, “Look and weep,” and “Lest we forget” encapsulate a sentiment that was common among liberators and still rings true today, a driving purpose of the Philipson Collection: Only by bringing the “evidence” to light — and very intentionally remembering andl earning from it — can we ensure that history doesn’t repeat itself.