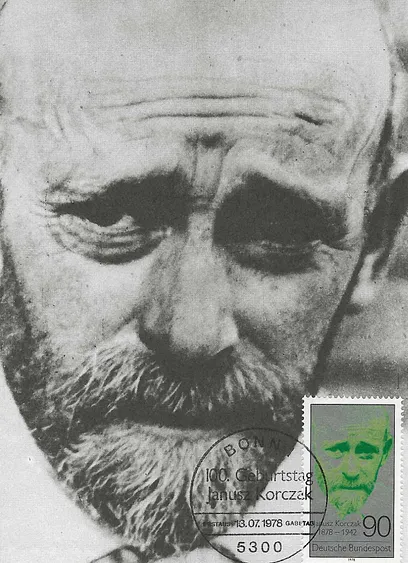

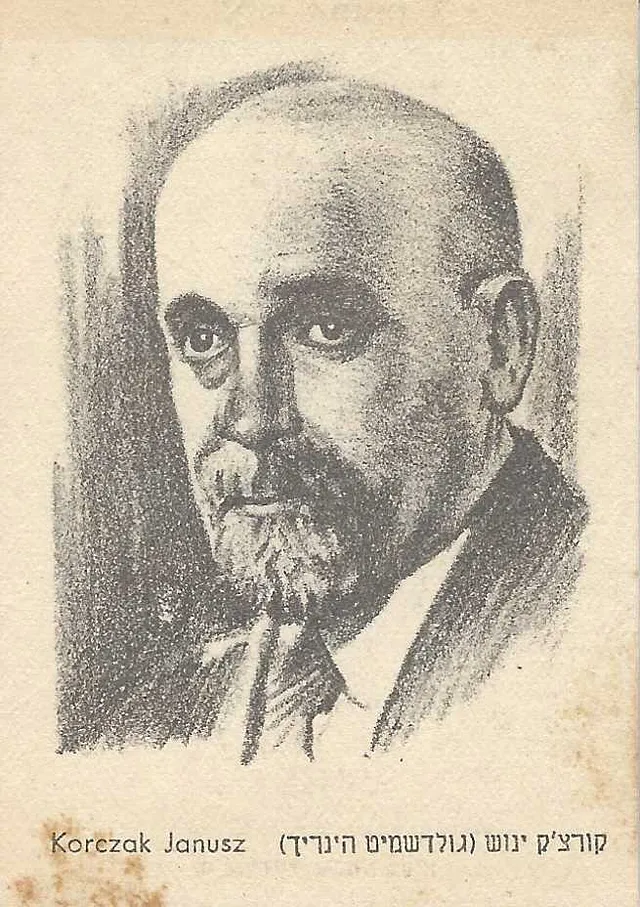

Born Henryk Goldsmit in 1871, in Warsaw,Poland, Korczak was a pediatrician, author, educator, and school master who advocated tirelessly for children’s rights. In 1898, he used “Janusz Korczak” as a pen name on his entry into his first literary contest.

His collection of writings extends from 1896 to1942, and is wildly varied in nature, comprising 23 books and about 1500articles, for both children and adults. His first novel, King Matt, was as popular in Poland as Peter Pan was in the English-speaking world. In all of his writings, the overarching theme is his steadfast belief that children deserve respect and should be taken seriously. “Children are not people of tomorrow; they are people today,” he wrote in his 1919 Declaration of Children’s Rights. His pedagogical writings are still seminal for educators around the world, and the UN’s 1989 “Convention of the Rights of the Child” is largely inspired by his writing.

Korczak was also a popular Polish radio personality, “The Old Doctor.” Throughout the 1930s, he spoke about education on the show, speaking to both adults and children in language even his youngest listeners could understand. Korczak’s “The Old Doctor” program’s final broadcast was on September 23, 1939, just a few hours before the Nazis silenced Polish National Radio during the siege of Warsaw.

Despite the breadth of his career, Korczak’s most profound legacy is his work with Polish orphans—and the loyalty he showed “his” children in the face of the unspeakable horrors of the Holocaust.

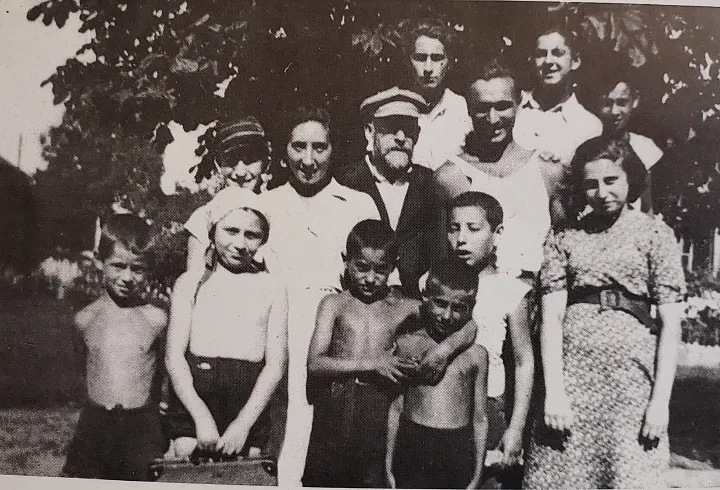

In 1912 and 1919, respectively, Korczak opened his two orphanages in Warsaw, Dom Sierot and Our Home. Jewish children between the ages of seven and fourteen lived at these orphanages while attending Polish public school and government-sponsored Jewish schools, known as Sabbath schools. The pedagogy Korczak used at both orphanages was centered around fostering children’s independence and empowering them to become experts at whatever interested them.

In 1940, after the German occupation of Poland, Korczak’s orphanage was moved into the ghetto. Korczak himself received several offers from the Polish Underground to be smuggled out of the ghetto and into the “Aryan side” of the city, but he refused to leave his children behind.

“You do not leave a sick child in the night, and you do not leave children at a time like this,” he wrote in his diary.

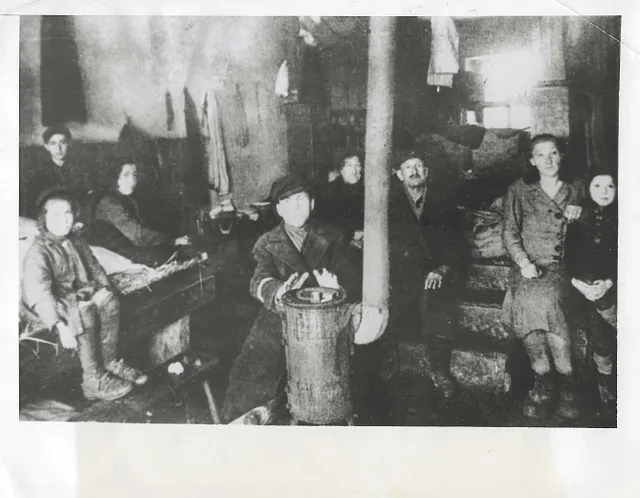

Conditions in the Warsaw Ghetto

Korczak's Last Walk

Nor did he leave his children on August 5, 1942, when German officers rounded up the nearly 200 children and staff members at Dom Sierot for deportation to Treblinka.

Korczak was once again offered the opportunity to escape. One story goes that an SS officer recognized him as the author of one of his favorite children’s books; another suggests that Nazi authorities had some kind of “special treatment” in mind for Korczack. Regardless, Korczak refused, instead enduring the four-hour march and boarding the trains with his children in order to comfort and care for them in this time of abject terror.

One eye witness, Joshua Perle, wrote the following of the scene:

Janusz Korczak was marching, his head bent forward, holding the hand of a child, without a hat, a leather belt around his waist, and wearing high boots. A few nurses were followed by two hundred children, dressed in clean and meticulously cared for clothes, as they were being carried to the altar.

(Quoted in Nick Shepley’s 2015 Hitler, Stalin and the Destruction of Poland: Explaining History)

Wladyslaw Szpilman also writes about the scene in his 1946 memoir, The Pianist:

He told the orphans they were going out into the country, so they ought to be cheerful. At last they would be able to exchange the horrible suffocating city walls for meadows of flowers, streams where they could bathe, woods full of berries and mushrooms.He told them to wear their best clothes, and so they came out into the yard, two by two, nicely dressed and in a happy mood. The little column was led by anSS man...

And, finally, the “poet of the ghetto,” Władysław Szlengel, who would die in the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, wrote a poem about “the last walk” immediately afterward:

I saw Janusz Korczak walking today,

leading the children, at the head of the line.

They were dressed in their best clothes—immaculate, if gray.

Some say the weather wasn’t dismal, but fine.

They were in their best jumpers and laughing(not loud),

but if they’d been soiled, tell me—who could complain?

They walked like calm heroes through the haunted crowd,

five by five, in a whipping rain.

[…]

How calmly he walks, with a child in each arm:

Gut Doktor Korczak, please keep them from harm!

A fool rushes up with a reprieve in hand:

“Look Janusz Korczak—please look, you’ve been spared!”

No use for that. One resolute man,

uncomprehending that no one else cared

—not enough to defend them—

his choice is to end with them.

[…]

Read the full translation here.

Korczak, always a champion of children, lived what he preached, championing his own children—the orphans of Warsaw—to the very end.

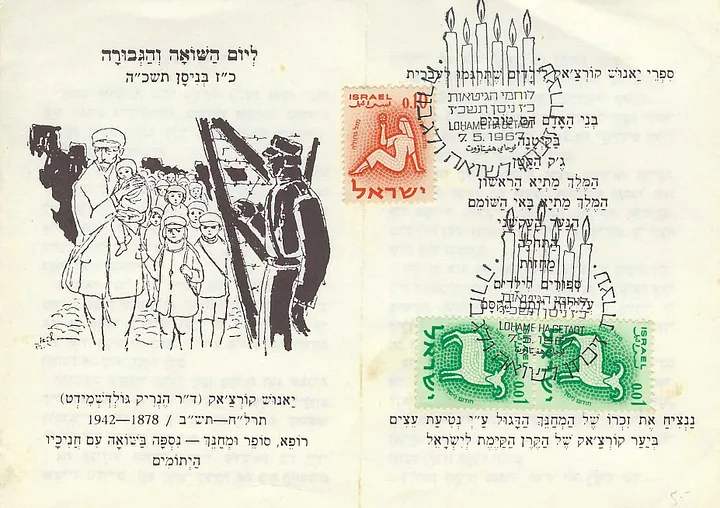

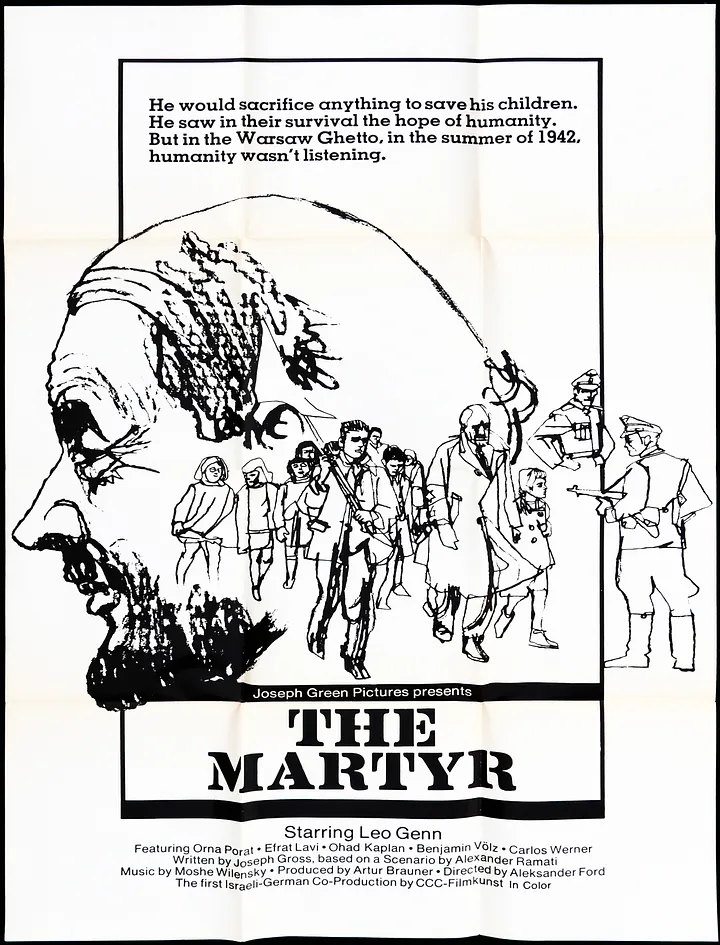

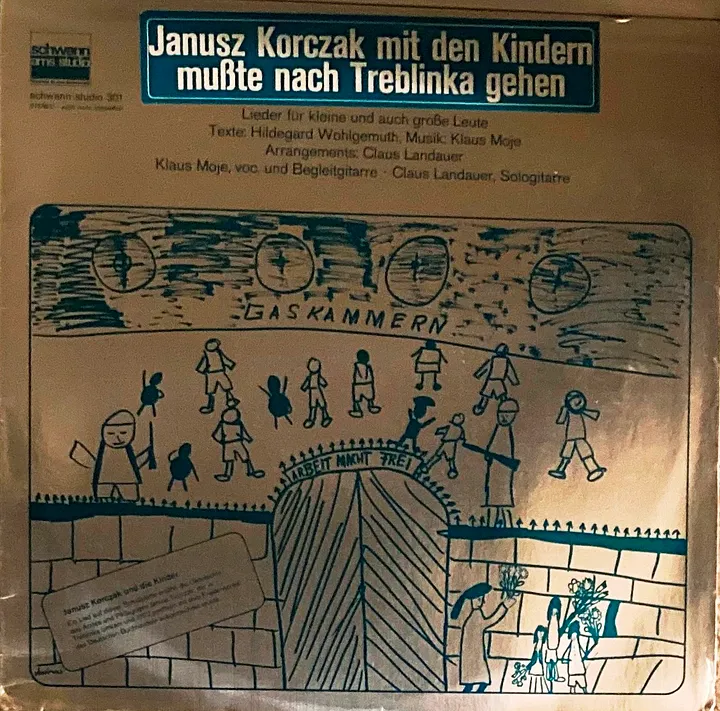

A Few of the Honorariums to Janusz Korczak in the Philipson Collection