While Nazi activity was most rampant in Germany, during the 1930s it was not contained there. Anti-Jewish sentiment spread all over the world — including the Vichy government in France, the Iron Guard in Romania, and the Rexist movement in Belgium. There were also plenty of influential political, industry, and religious leaders in the United States, including Charles Lindbergh, Henry Ford, and Charles Coughlin, among others, who were anti-Jewish, pro-Nazi, anti-Roosevelt isolationists. This global support — active or tacit — for the Nazi party and its principles contributed to their ability to achieve a stranglehold over German life.

.png)

Denmark

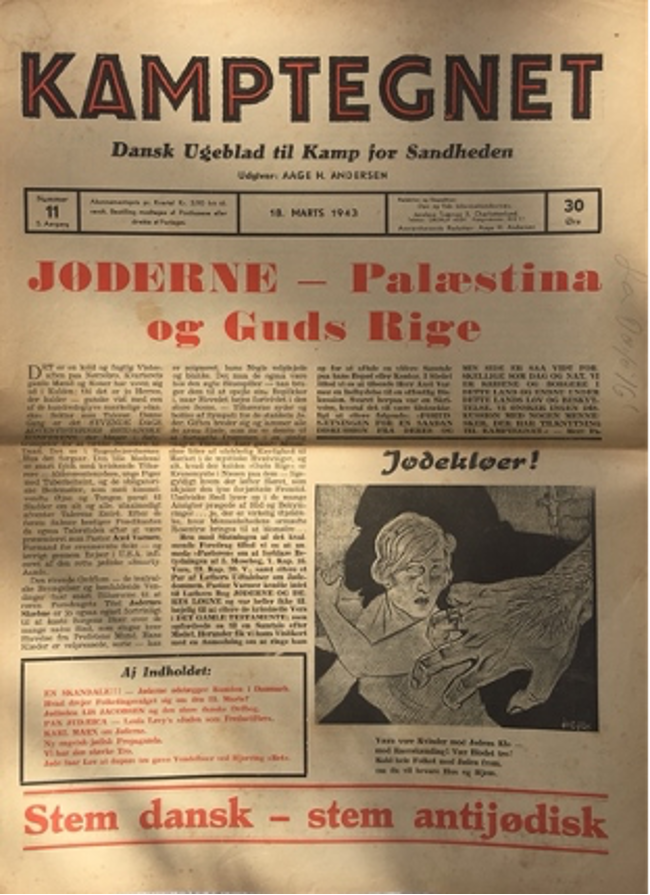

Even in Denmark, where one might suspect Jewish people would be safe, anti-Jewish sentiment led to propaganda items such as these national socialist party labels (first picture below) and this newspaper (middle) depicting the Jewish holiday of Purim as a ghoulish cartoon.

The newspaper above, Kamptegnet (“Battle Journal”) was essentially a carbon copy of Der Stürmer (below), from design and format down to the tagline. Many editions feature the Danish version of Der Stürmer’s tagline, which translates to “The Jews are our misfortune.” The issue pictured here is tagged, “Vote anti-Jewish,” and the publication rotated through several similarly hateful slogans. Like Der Stürmer, Kamptegnet had nothing to do with actual news — its only content was hate.

Nazi France

In France, while the Nazis occupied the northern portion of the country, the Vichy government maintained control of the south, but make no mistake: they were doing the Nazis’ dirty work with relish. As you’ll see in a future post, when it was time to round up the Jews in Paris, it wasn’t the Nazis doing the job, but the French gens d’armes.

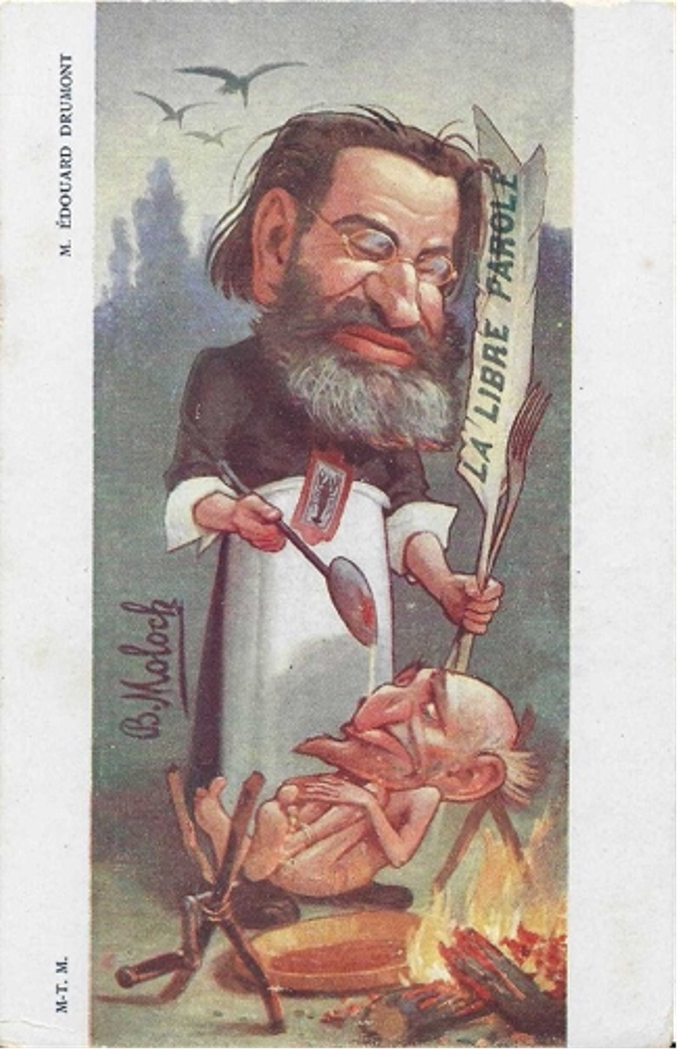

These two French postcards, both produced in 1898 and featuring France’s most notably anti-Jewish journalist, Edouard Drumont, highlight the anti-Jewish sentiment throughout Europe, even long pre-dating WWII. The first (above) is a grotesque representation of the Dreyfus Affair, and the second (below) depicts a gross caricature of a Jew’s head on a plate, being eaten by Drumont the crusader.

.png)

Anti-Judaism in The United States

America was not without its own anti-Jewish sentiments. Here are just a few of the endless examples in our collection.

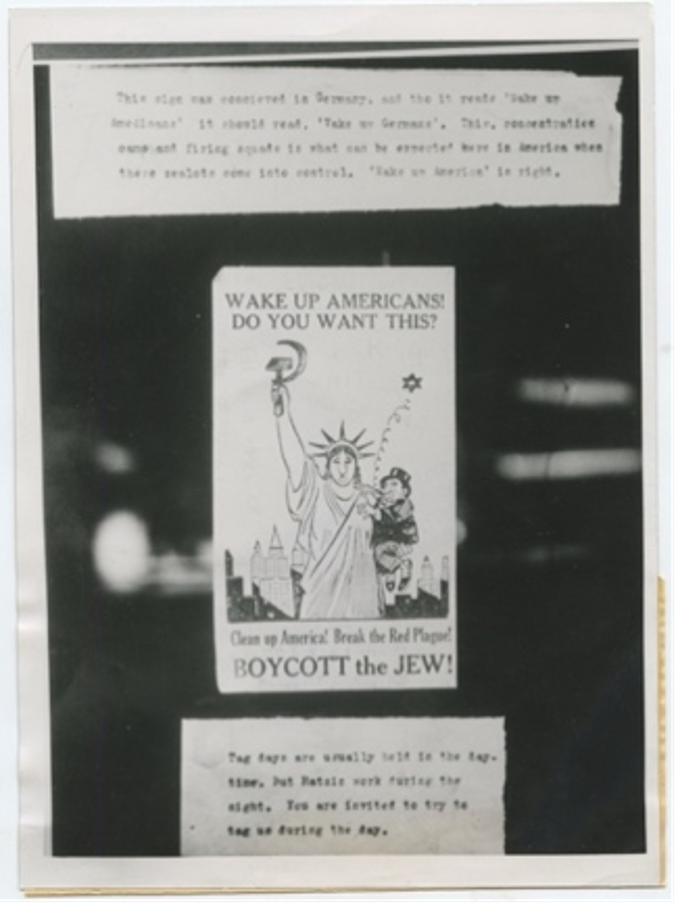

This “Boycott the Jew” sign could be found on a store window in Portland, Oregon in 1938, shortly before Kristallnacht. Referred to in English as “Night of the Broken Glass,” Kristallnacht took place on November 9 and 10, 1938 when the Nazis called for a series of pogroms (waves of organized violence) against the Jewish people throughout Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia (source). The name, “Kristallnacht,” refers to the shattered glass lining the streets in the wake of the massacres, which targeted synagogues, Jewish homes, and Jewish-owned businesses, killing scores of German and Austrian Jews.

Charles Coughlin

.png)

.png)

Charles Coughlin was a Catholic priest based in a suburb of Detroit. He was also vocally anti-Roosevelt (joining other leaders who nicknamed him “President Rosenfeld”), isolationist, and anti-Jewish, linking Jews to communism and spreading the idea that, among various other crimes, they manipulated the economy for their own gain.

Henry Ford

.webp)

Titan of industry Henry Ford was loudly anti-Jewish, as evidenced by his 1926 editorial in The Dearborn Independent, “What About the Jewish Question?” and his two volumes of anti-Jewish essays, The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem and Jewish Activities in the United States, both also published by The Dearborn Independent.

.png)

Ford’s essays were based in part on a fictional series called The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, published in Russia in 1903 and still used by radical Islamic groups today. The essays blame Jews for all that is wrong in society and accuse them of a conspiracy to take over the world (source). The Protocols were a cornerstone of the Nazis’ propaganda initiatives in the ’20s and ’30s — the party published more than twenty editions of the book, and many schools used it to indoctrinate students, as well (ibid).

German Amerca Bund

%20-%20Sarah%20Welch%20(1).png)

.png)

The German American Bund was a pro-Nazi, anti-Jewish organization of Germans in the United States. The potograph above is of their leader, Fritz Kuhn, speaking in Milford, New Jersey. It is estimated that the Bund had 25,000 members, and they were active in spreading anti-Jewish propaganda through rallies, publications, and Hitler Youth-style camps for children, one of which, Camp Siegfried, was on Long Island (source).

.png)

%20-%20Sarah%20Welch%20(1).png)

%20-%20Sarah%20Welch.png)

%20-%20Sarah%20Welch.png)

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again.

When we talk about what the Nazis did, we’re really talking about the Nazis and their far too many collaborators.

The murder of 6 million Jewish people — not to mention the Romani people, homosexuals, communists, people with mental disabilities, and prisoners of war, along with anyone the Nazi party deemed enemies of the state — required cooperation from across the globe.

Keeping that kind of hatred at bay requires cooperation, too.